Mariken Wessels spoke with me about her work and evolution as an artist. Here is our conversation:

epd: When did you start making visual art works, and how did you start working with found materials?

MW: Before I moved to Amsterdam to attend the Theater School I was already taking photographs. In the southern Dutch city of Breda, where I grew up, I worked in the small local theater, where each employee had multiple responsibilities, from door keeping and preparing the dressing rooms to constructing the sets and serving coffee during the breaks. This small theater was part of a larger theater where large companies were holding their rehearsals. At the time, in the early 1980s, I was able to attend every show, by both small and larger companies. Due to my job I was allowed to take pictures during rehearsals too. I felt intrigued by the narrative power embodied within theatrical scenery, which prompted me to move to Amsterdam to study acting at age twenty. A few years later, after having graduated from the Amsterdam Theater School I studied a year abroad at the Lee Strassberg Institute in New York City. During my subsequent acting career in The Netherlands, where I worked for classical theater as well as for T.V. series, I kept on taking photos. Additionally I was involved, like during my apprentice years in Breda, in everything dealing with a play, from suitable attire to the design of sets. This attitude was stimulated at school and also welcomed in practice.

Parallel to my acting career I kept making my own work, which grew stronger and stronger on its own, up to the point that I realized I’d be happier on my own and let my art works develop within an autonomous practice, rather than remain part of the bustle of theater. And I went back to school, this time the Rietveld academy of arts in Amsterdam. One of my teachers in the photography class assigned us to make a book. At that moment I realized I wanted to make a book about someone dear to me who passed away, but of whom I had no photographs at all. On the internet I started searching for photos related to his everyday surroundings. I worked from the outside toward the interior, as it were. I asked myself the same questions that I would have asked myself in the capacity of actress. By means of these questions I tried to build a picture of this person, adding to the portraits pictures that approximated the way he lived, where he lived, how his room looked like, and what things he used. He played the guitar and listened to cassette tapes a lot, so I went looking for these kind of images, too. And I found exterior shots of his house. This collecting activity helped coming close again to this dear one I’d sadly lost. I collected the images I found in a little artist’s publication. One of the results that fascinated me is how the images in this book replaced my actual memory of where and how he lived. When I think of the staircase in his house or his room, my mind is directed to the book. I discovered the frightening possibility of pasting images onto one’s memory, distorting that memory toward a belief in the later images rather than the actual, living memory. Even though human memory is unstable to begin with, the idea of memories being replaced by (other people’s) photographs is something that kept me busy ever after. This launched my interest in ‘found footage’ and convinced me that other people’s images, often anonymous, can be easily appropriated both into my artist’s practice and into my private memories. I realized that anybody’s image could become everybody’s image.

epd: You studied and practiced as an actor for many years. How has that influenced your art practice? Does your experience as an actor affect your artwork, especially through your use of narrative or embodiment of a character through photography?

MW: I think that the way in which I work has a lot to do with how I was trained as an actress in approaching a t

heatrical role. Just like an actor has to study and do research in preparation of a role, I invest a lot in research and preparation for a project. I collect as many materials as I can around a certain theme or initial body of work. I have a large, Styrofoam bulletin board in my studio onto which I paste those research materials that might turn valuable for a project. Then there are large tables on which I collect objects or books that might become part of the story, or as attributes to a character.

In order to collect materials I’m reading a lot, comb out the internet, and my own memory or notebooks, because usually a lot of information and material has already been collected before I could connect it to an outlined project.

The molding of a character, to give it emotional depth and a credible environment (or a set, if you wish, to stay in the realm of theater), is stimulated by employing the Stanislavski-method of an actor’s preparation, following the so-called five W’s (Who am I? Where do I come from? Why do I do what I do? What do I do?, and When?). Thus one creates a faithful being, one who deals with trauma, has memories, goals in life, and so on. This digging of the human soul is what interests me and gives me the freedom to invent as much as it establishes the framework with which to keep a possible surplus of invention at bay.

epd: We are currently featuring the books included in your trilogy box in our exhibition Je est un autre: The vernacular in photobooks. Why do you consider these books (Elisabeth – I want to eat; Queen Ann. PS Belly cut off; and Taking Off. Henry My Neighbor) to be a trilogy? What are some of the differences or similarities between these three books your other work?

MW: All three books deal with people experiencing difficulty in keeping their lives on track and each of them deals with problems in a personal way. What binds them together in the end is a desperate cry for love and attention. But in each of these stories this attempt at healing happens rather falteringly. To be able to participate in the ‘normal’ world of daily goings-on doesn’t go without saying. The threat of dropping out is always just around the corner, one false step and one’s pushed to the side of the road. The border between functioning normally and failure is razor-thin. A repeating motif in my work is constituted by life’s vulnerability and contingency. The role played by memory and how people, especially under dire circumstances, find creative ways to shape and reshape a memory of a tragic event or their discontent, is a recurrent theme as well – perhaps the most important propeller of my pictorial approach in combination with first-person written statements accompanying the images as, for example, personal letters, postcards, or snippets. We often come to believe in our, often deliberate, distortions of our memories as conveying the truth. But I tend to place big question marks at such a belief. To what extent can we trust our memory? How can we even be sure that something has happened in the way we remember that something? As memories seem to buttress our feeble existence, that existence can easily collapse when memories prove to be fictitious.

Finally, another important theme is the way in which people communicate, especially when that communication seems inadequate. In Elisabeth –I want to eat (2008), for example, the eponymous character conducts a correspondence with her aunt Hans in order to keep a lifeline to the outside world, while she gradually gives in to depression. Hans approaches her niece as if she’s a patient, but her peculiar way of communicating raises the question who’s actually in need of help here.

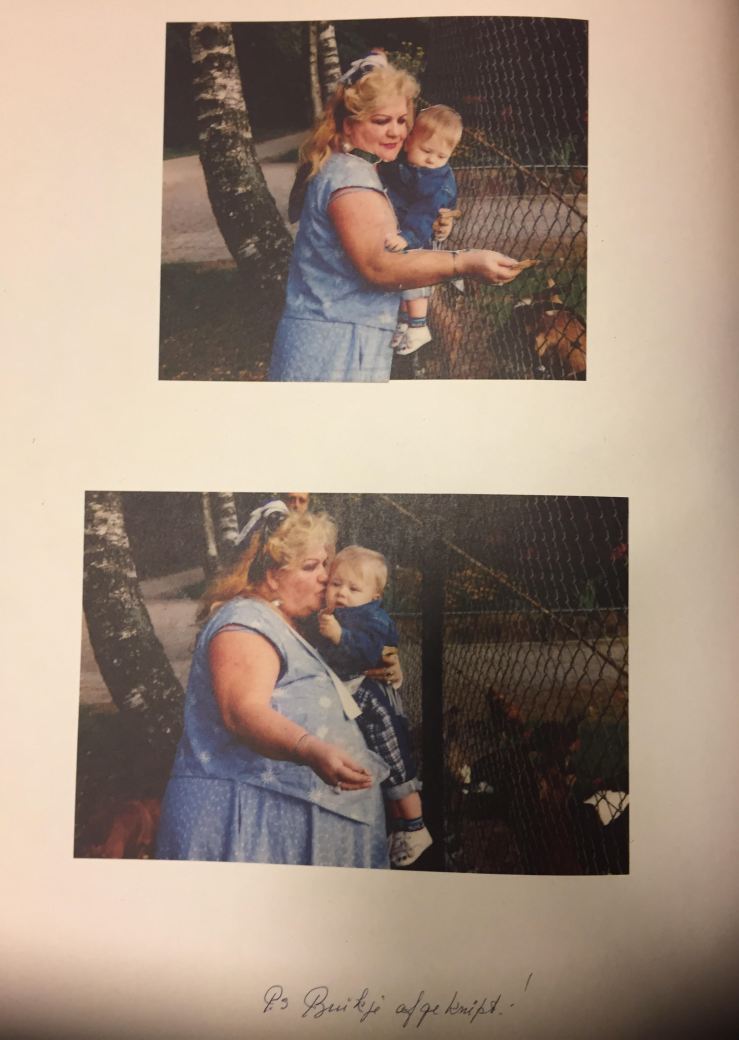

Ann, the protagonist of Queen Ann. PS Belly cut off (2010), the second book in this ‘open trilogy’, tries hard to keep a handle on life, but only with immense difficulties. She keeps safe distance to the real world and shapes her own world in which she attains her youthful and slim beauty again. Almost voodoo-like she cuts off her belly from recent photographs, damages her image so to restore her self-image.

In my latest book Taking Off. Henry My Neighbor (2015), we are witnessing Henry and Martha’s marriage becoming marked by the camera as an increasing divisive force. Henry almost literally disappears, firstly behind the camera with which he photographs an undressing or undressed Martha, secondly behind the prints he arranges into sequences and patterns, and after Martha has left him behind, Henry tries to reassemble her image into weird collage works before he retreats into the forests never to be seen alive again. I think that the ways in which he obsessively and systematically annotated his photographic project amounted to a frenetic effort to cling to life, while it would come to cost him his marriage.

epd: Your work in the trilogy deals with found materials, the origins of which are somewhat explained on the colophon, but not within the narrative of the story. Can you talk a bit about the process of discovery of these materials, and how you go about selecting a set of materials to investigate?

MW: I trust my “antennae” to be on edge when encountering potentially interesting material. It’s a process I find hard to analyze or describe in detail, as it works so intuitive and guided by associations, that a single found or given photograph could carry the seed for a large work, whether it be a book, series of collages, a sculpture, photo series or otherwise. One thing leads to another. Recently, on the occasion of an exhibition at the The Hague Museum of Photography where I reshaped this ‘open trilogy’ into a spatial installation, I reworked the materials I’d used for Elisabeth –I want to eat for a 17-minute long film called Elisabeth (2017).

epd: In all of your work, I am consistently struck by the strength of your sequencing and narrative. Your ability to use blocks of images as markers or chapters to break up different elements of the story is especially powerful. What is your process when you are choosing the ordering or sequencing of imagery for your books, especially Taking Off and Queen Ann?

MW: As I said earlier for my researches I collect various materials, but I also produce images myself. Combined, these are added to my ‘sketchbook’, which consists of a long wall in my studio. The arrangement of the materials evolves from mood-board to storyboard, following free association as well as based upon research, developing into a story whose features grow sharper. In this process of questioning and polishing and honest listening to myself, I constantly wonder whether certain interventions are right. This process at times is very tedious, but I see it when it’s right.

When I make the transition from storyboard (still a spatial lay-out) to the book format, I scan or rephotograph all my materials before I make several dummy versions in InDesign. For all my books I did the sequencing, lay-out and design myself. I print paper dummies to check if the sequencing and design works well outside the computer too. When I transmit this dummy into a real book with a published, usually very few changes are made to my original concept.

epd: Have Martha, Henry, Anne or any of the other subjects of your books seen the finished pieces? What has been their reaction, or their families’ reaction?

MW: As far as I know none of them, nor their direct family members, has seen any of my books. At least, I’ve never gotten a response nor spoke to anyone who has heard that my subjects have had access to my books. And, honestly, this is not what I’m after, as the material has been removed (and often already far removed when found) from its original context and gone through my process of appropriation.

epd: Your books are often described as “voyeuristic.” I find that this description is a bit limited, and have always had the impression that you feel a certain empathy or tenderness towards your subjects. Can you discuss the nature of voyeurism and empathy in your work, and how you go about finding a balance between the two?

MW: The interplay of voyeurism and empathy is important in my books and it plays out on many levels, directed towards how a ‘reader’ of my books might feel about witnessing the collected material and the story but also voyeurism and empathy as it plays out with or between my subjects. I’m very much interested and stimulated by people and their, often strange, behavior – especially of people whose condition is hanging in the balance, so that distinctions between what’s normal or deviant are much harder to make.

For example, in Taking Off it seems as if Martha is being exploited through her husband Henry’s nearly ceaseless interest in using her as a model, but it is she who decides to put an end to it and even disappear from his life and their marriage completely. She stands her ground and takes over control.

I think it is thanks to my education in theater and acting experience that I can place myself quite well in other people’s shoes. Also, the characters in my book are often not far removed from characters I know in my own life or from my own experience.

epd: I was exploring your sculptural work and was struck by your piece Recover. Your website describes it as follows: “This is a leaf with a hole in it. One of Mariken’s hairs has been used to repair the leaf. Via this one simple act Mariken is attempting a grand gesture; to counteract mortality and to ask for forgiveness.” Your interventions are so elegant and respectful of the story, be it about a marriage, a teenager or a single leaf. I wondered if you could touch on the themes of rescue and repair in this work and in the work that appears in your photobooks.

MW: It’s all about holding on to things and memories, to not wanting to let life pass. It’s about fear for departure, fear of losing someone dear to you. Perhaps the holding on is convulsive, but that also bears the seed for tragicomedy.

In Recover I wanted to heal something with something very close to myself, my own hair in this case, but a strand of hair is frail. In this work I arrived at a fragile balance. In fact, in life one can never have a full grasp of or hold on things. Life can sneak out any time, suddenly, and then you’re left with empty hands. Recover constitutes an impotent attempt, a cry from the heart toward a better handle on life with its inevitable losses.

epd: Themes of body dysmorphia and anxiety appear often in the trilogy. Do you think that the reproduction of one’s image, and the power of manipulation of that image, speaks to these themes?

It does so indeed. I’m interested in distorted self-images. One can feel very different from how one appears (to yourself or others). This type of schizophrenia doesn’t always come to the fore in everyday behavior. What I want to show is behavior that gets marked and distorted by despair, as can be evidently seen in Queen Ann who wrestles with her self-image and cannot accept that the times of her juvenile beauty are irreversibly gone. She still wants to wear a sailor suit because it was denied to her in childhood. When she dresses in a sailor suit she feels young and small. Everything is possible and things are yet to get started. As her adult life bears too heavy on her, she creates her own world, or recreates a warped image of childhood. And Queen Ann is just one example standing in for many anonymous others wrestling with issues related to low self-esteem.

I’ve recently been reading an interpretation of Hans Bellmer, and his photographs/sculptures by Sue Taylor, she writes that Bellmer’s work can be read as feminist and that Bellmer, and therefore his depictions of his doll is “…thoughtful, well-read, and sensitive individual, a real intellectual.” and that his work is not based in misogyny, ownership and manipulation of the female body. Do you think the same instinct is present in Henry and his story? Is he trying to identify with the female body?

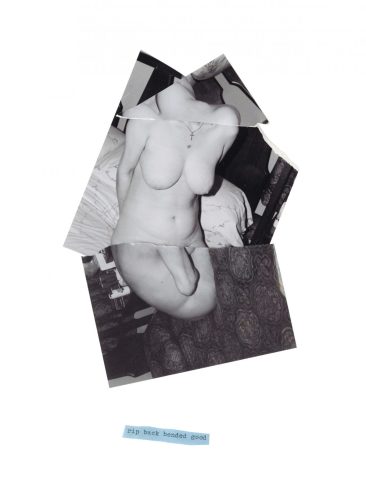

I find Bellmer an intriguing artist. I even possess two works by him. But to answer to your question: After Henry’s wife and muse, Martha, had suddenly left him alone, for Henry also the ‘object’ disappeared which gave his obsessive lust for photographic registration outlet and focus. Instead of looking for a replacement model, Henry gave free [reign] to his obsessions in relation to all the remaining photos, including the fragments he gathered after Martha had left behind a torrent of images thrown out the window. It is perhaps in this period that Henry ‘discovered’ his artistic talents by assembling collages based on the thousands of nude pictures. I think it especially came to pass when he, presumably by accident, overlayed multiple torn images.

Very different from what could be expressed through a single photograph, we see a Henry emerge who vented to his lustful desires by focusing on breasts and buttocks in particular. I, for one, got very curious about the boundary between obsession and sexual desire on the one hand, and the self-discovery of Henry the ‘amateur’ artist. I’m not sure that he was even aware of such ambition when still together with Martha.

In a certain sensitive approach to this dangerous subject I do see similarities to Bellmer’s work. Like in Bellmer’s case, Henry’s figurines (based on his collages based on his photographs of Martha), can be of classical beauty while they are permeated with some kind of serenity.

Have there been any collections of found materials that you’ve begun working with that did not manifest in a project?

Nope. But I won’t exclude any option since that would place a limit on my artisthood.

epd: Are you working on any projects now?

MW: Currently I have several projects running, based on gathered materials waiting to be fully formed and realized. These are put on hold for the time being since I’m working on another project since last summer which eats up all my time and attention for now. I won’t say much about it except that it will be presented in the course of this year and the next in three different phases.

The first presentation will consist of a few life-size ceramic sculptures based on the human body. These will be on show as of June 2018 in Museum Princessehof in Leeuwarden, The Netherlands. These sculptures are inspired by one of Muybridge’s plates from the Human and Animal Locomotion series, namely plate 268, titled ‘Arising from the ground’ (1885).

A sculpture, of course, stands still. But there’s a major difference between a static presentation or a movement that is ‘frozen’ in motion. The latter type of ‘movement’ can be completed in one’s own imagination. Sequence and time are important elements, hence Muybridge.

https://www.marikenwessels.com/uploads/videos/00010.mp4

As of the early summer I will start working on a project following from this first presentation. This must become a photo series in which the human body will be explored in its ‘scenic beauty’ as well as in its animal nature. Keywords here will be deformation, (absence of) gravity and the elegance of the unexpected.

In the third phase I want to make a publication in which the first two series (sculptures and photographs) are brought together. Finally, the different stages of this project will be contained within a larger project.

epd: Lastly: What is your astrological sign?

MW: Sagittarius.

photos courtesy mariken wessels / image copyright mariken wessels

Brilliant – thank you for this in-depth interview that includes the inspirations for some extraordinarily penetrating creative understandings of lies on the edge.

[…] anybody’s image could become everybody’s image: an interview with Mariken Wessels […]

[…] tout cela ? L’artiste néerlandaise Mariken Wessels, qui a déjà réalisé plusieurs séries autour de photographies trouvées, aurait obtenu ces photographies, ainsi que d’autres images du couple, de leur maison et de […]