To say that Mariken Wessels’ work did not plant the seed to put on our exhibition Je est un autre: The vernacular in photobooks, would be a lie. Wessels work takes a collection, examines it with a considered eye and presents it carefully. For me, where Wessels work transcends from printing a collection in book form is how she introduces herself and an unreliable narrator, which in photography involves the act of manipulation.

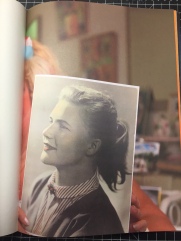

This comes up in both Queen Ann. P.S. Belly Cut Off and Taking Off: Henry My Neighbor (Which I will be writing about later, and have been obsessed by all year.) Looking at Queen Ann again, I noticed the images that place the element of doubt, visually. An image of a woman in the water, beside a dock, but there is a second reflection in the water–Where is that person? In another photograph, possibly a double exposure, a ghost of a woman stands in the woods. Who manipulated these photographs? Was it Wessels, or was it Queen Ann? We begin to learn that Ann herself is fond of altering her own images: We see a family portrait where she has painted makeup and some hair on her mother and collaged a sailors suit on herself, as well as subtle examples of manipulation such as cutting out faces or obscuring them. Anne wrote on the image of her and her mother: “I drew myself and I drew myself a sailor suit. At my First Communion I wore a sailor’s dress, sadly enough no one took any photos it just wasn’t done in our days. Back then there was (no money and no worries) my father sand that all the time, well, it was just after the war.” We learn that photography and memories are important to Anne, and she finds her interventions a way to correct history.

Then we are presented with a mystery. A series of dark and potentially violent images break the narrative. A woman runs, topless through a field or possibly on a beach, is seen touching her breast, while a nude man is also introduced. The tone in this section of the book is remarkably different than the previous and series that precedes it. The only clue that I can guess at is from a caption Anne has written about a man about her age named Piet: “HI our Piet – p.t.o. Sadly met with an accident he appeared to me in a lightweight body. I’ll tell you some time.”

The reader is then re-introduced to Anne, but time has passed (the dark and mysterious photographs we just saw?) and Anne is holding a hand tinted photograph of herself. We see Anne hiding behind portraits of her younger self with a drawn on mustache and freckles. We are then finally introduced to Anne as an older woman and her artistic interventions in her portraits. Anne’s style is bright and poppy. She often paints scarves or head wraps that conceal her chin, implying that she isn’t pleased with her appearance in the photographs and adjusts them accordingly. However, body image issues aside, Anne’s interventions in her portraits are beautiful, she has a recognizable style and is extremely funny. In one image, she stitches two stills from a television and creates a small self portrait with a drawing of her torso montaged on top.

The last section of this narrative is Anne running through a fall scene. The aesthetic is similar to the dark scenes in the previous section, but the images are in color and Anne smiles and wears a bright red poncho. Perhaps Anne has transcended the dark period of her past.

Of course, this is all conjecture. There is little text, save for Anne’s captions or notes written on her photographs. My reading however, is that this is a transcendent story and while there are elements of pain in Anne’s history and she has some disappointments with her appearance, she is not an unhappy woman, and is in her heart an optimist. The last caption she writes “Is there any hope for me?”

[…] Mariken Wessels: Queen Ann. P.S. Belly cut out […]