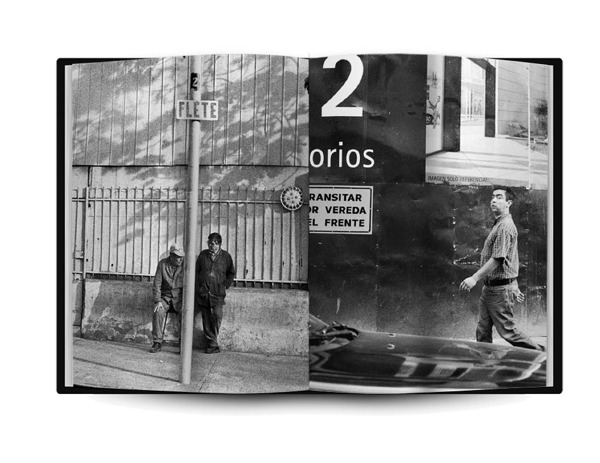

Illustrations from Luis Weinstein’s previous book titled Aritmética Americana. Images he took in different countries when traveling South America. It was published by CenFoto, Chile, in 2012.

Photography is a term that, like the photographic image itself, represents many things. Probably because the medium, made up of many layers of meaning and social functions, is an invention of modernity, we are still lacking the idiomatic subtleties to separate out all the parts united in that word. On the one hand, fotografía is an object you can hold in your hand; on the other, fotografía(“In Spanish, fotografía is both the term for the photographic object and the discipline of photography”) describes an entire discipline and in addition, the symbolic production of a contingent of users.

When we read “South American,” we understand it to mean belonging to a space made up of 12 sovereign countries. Therefore, when we say “South American photography”, combining two enormous concepts, we are speaking of many things at the same time and, with neither the intention nor the ability to be exhaustive, I would like to pause to consider some of them. The first reductionist trap we tend to fall into is to think that a “photograph” as such exists once we click the camera shutter,but if we consider that the photograph, in addition to being an object, is also a form of communication (perhaps even a new form of language), then in order for it to come into being,the shutter-clickis necessary, of course, but so is processing, and, fundamentally, this technological object, loaded with symbolism, must circulate. Stashed away in the bottom of a box, a valley, or an isolated continent, it does not develop its full potential.

The (minimal) circulation of South American photography, or Latin American photography in general (with the possible exception of a few Mexican artists such as Manuel Álvarez Bravo or Graciela Iturbide) is, in my opinion, one of the definitive characteristics of this cultural production. It is here that all the terrible weight of the vast difference in wealth and influence between the developed countries and our own is brought to bear—the differential that in the arena of political economics and sociology has given rise to all the theories of “center and periphery” or, more generally, “developed countries vs. third world”; our inarguable inclusion in this non-hegemonic sector of production and consumption of all types of goods, and consequently our minimal impact in western globalized Culture, has marked our behavior as creators, our cultural practices and especially, the miminal circulation beyond our borders of our cultural production in this field. Essentially, we have only looked at ourselves from within each individual country, even when our imaginaries have been influenced by the artistic creations led by the hegemonic cultural avant-gardes of the West. We are a passive choir, whose echo is only heard amongst ourselves, with respect to this global influence. Until recently, in the analogous pre-Internet era from which historically we are just emerging, we lived almost exclusively surrounded by each other.

Symptomatic of this phenomenon is the fact that photographers from the United States, in biographies and reviews, are identified as “American photographers,”as if all of us, the inhabitants of the enormous Latin America, were not as well; the fact that “people of the United States” is exclusively synonymous with “American” shows to what extent our production, and existence, is inivisible in the greater world.

In August of 1839, Daguerre went public before the French Senate with his invention ofthe process for obtaining images “directly from reality,”andalready by January of 1840 this cultural virus had arrived in the Southern Hemisphere aboard the French frigate L’Oriental, which set off into the world with two cameras, and installed photography as a cultural practice on the subcontinent. This frigate sunk in the bay of Valparaíso, within the confines of the Pacific Ocean—a very South American act of self-destruction, for sure—but the cameras and the crew survived unharmed and the rest is history.The existence of Hercules Florence and his independent invention of a photographic process in Brazil in 1832, investigated by Boris Kossoy in the 1970s, does not substantially change the official story; on the contrary, it confirms that both a physical object (the image on paper, glass, or metal that Florence did develop) and its circulation (which Florence never achieved on a sufficiently large scale) are necessary for us to be able to speak of “photography” in the sense of an archive of images, given social meaning and recognition and representative of a regional practice.

More than 170 years since the germination of that original seed, the daily practices connected to photography possess a great vitality in all of Latin America. The technological advances of recent years have been fundamental in achieving this level of penetration, since the possibility of multiplying shots—no longerdependent on the cost of processing the film and the copies—together with new options for circulation made possible by digital space, opened the doors to a vast group of users who communicate through the medium on social media and through electronic publications.

In a continent where large social sectors have lived for centuries at the margins of the dominant written culture, where education is always under the magnifying glass—as much because of doubts about its quality as for the economic difficulties of gaining access to it—this new technological possibility for communicating efficiently, economically, and with immediacy across vast territories (to give just one example, if Chile were superimposed onto Europe, from top to bottom the country would cover from the northern part of Norway to Algeria)proves to be very attractive. The existence of a consistently expanding group of users and of elaborate practices of social circulation undoubtedly results in an increasingly dense and prolific artistic practice.

In our nations, as in many others, photographic activity began with portrait-taking establishments in the 19th century, which shortly expanded to include the capture of landscapes and picturesque scenes for the graphics industry once the reproduction of halftones made industrial printing possible. This initial nucleus was essentially made up of a small number of professional photographers, accompanied in this practice by a few wealthy aficionados enthralled by the new technique.

By the 20th century, when the industry had developed sufficient technical capabilities to provide the market with factory-produced sensitized photographic materials and newspapers were able to illustrate their texts with printed images, two new groups of photographers emerged: on the one hand, graphic reporters who fed images to mass media publishers, and on the other, a group of aficionados—no longer limited to rich heirs—who began to practice the new techniques. Around the 1940s, in numerous Latin American cities, photoclubs began to form where these aficionados, essentially members of the emerging middle class, often showed their work in contests and exhibitions (this being the form of circulation for their photographs). When this group of practitioners grew beyond a certain critical mass, their production inevitably expanded beyond this small circle and, led by some of the more connected members, the photoclubs were able to exhibit the creationsof their members in public places such as museums, galleries, and cultural centers.

This penetration of the new form of representation into the world of Art, with its consequent emerging acceptation as a vehicle of symbolic meaning,meant that photography was soon occupying the space of a cultural referent for our societies, to the point of attaining a very important position in the construction of our national identities.

Not long ago, I brought a copy of “Sueño de la razón” (“Dream of Reason”), the collective regional magazine we have edited since 2009, to a member of an important photography foundation in the United States. After glancing through it, he asked me, “Why so political?” The answer that occurred to me was, “because this is the most interesting photography being done in South America.” In truth, an important part of our self-conscious photographic production—in this sense we could also speak of art photography—revolves around political topics, in the broad sense of the word. Numerous South American “art” photographersput their greatest effort into making a political statement with their works, in many instances establishing a critical relationship with the existing order, whether it be through series of documentary-style denunciations or with works of staged photography that position themselves in relation topower and its consequences, whether it be in the area of the environment, gender, or questions of social marginalization and exclusion. At heart, it seems to be that a certain hope regarding the capacities of the medium as a vehicle for social change or transformation accompanies this creative endeavor.

This “political” use of photography has deep roots in South America and it seems to me that its defining characteristic isa certain urgency on the part of its creators to respond, using these tools of the trade, in the face of the demands of civil society: artistswho constitute themselves discursively as cultural mediators, whether it be through enunciating demands of political powers and the State, or as spokespersons of a deep sense of a lack of a State among large sectors of the population.

In other cases, this “political” gesture is at the formative level; the creative work posited as the bearer of a liberating discourse, one that should be “communicated” to the dispossessed in order to support their building of class-consciousness “for themselves”: in other words, a militant Art, for which photography and its supposed capacity for transmitting “reality” is a demonstrativetool of the first order, above all considering the high illiteracy rates and low levels of reading comprehension among a significant percentage of our citizens.

Another of the characteristics particular to the photography of our region is also described y Ronald Kay in his noteworthy essay “Del espacio de acá” (“From/about the space over here”). This invention, which emerged from the technological developments of the industrial revolution, is, when it crosses the Atlantic towards the lands of the south, confronted by a pre-industrial landscape. What gets represented in our territories in the early years of photography in our region is “exoticism,” the “picturesque” nature of our native ancestral and peasant customs, which no longer form part of daily life in the industrial societies of the first world. Our photographic production alternates between these modes of representation and social uses. On the one hand, the recording of exoticism as an image of our reality for export; on the other, as a tool for social agitation and denunciation of the great inequalities experienced South of the Rio Grande.

In both cases, our photographers are overwhelmed by a sense of the image’s urgency: what matters is to continue on with the project, to use all available creativity, in order to overcome the enormous material difficulties that cultural creation projects face in countries where the basic necessities of the population are not met. It is not easy to divert money to the capture, printing, circulation, and exhibition of photographs when scarce resources compete with the daily necessities of food, housing, and shelter.

The solution often involves low-cost printing and circulating the images by hand, so that not only the content, but also the form of the photographs are modified by the conditions of production and the reality from which they emerge.

One of the best strategies for taking on these social conditions that characterize our photography has been the development of collective and non-profit projects: collaboration between multiple actors allows for the negotiation of many difficulties, especially those related to the circulation of images, but the price to be paid is that the artists cannot make a living from these projects, as it is professionally unacceptable to charge for work destined to build awareness of a problem or to denounce an abuse. The collective that is willing to help demands equality, also framed in these terms, in the conditions for participation. The Common Good excludes, and takes priority over, individual profit.

What is most surprising is that this voluntary nature, characteristic in so many instances of photographic work, does not prevent new urgent, impassioned, and poorly compensated collective initiatives from joining every day the archive of work done in South America.

In summary, we are living in an amazing age, made possible by the new technical means for capturing, editing, reproducing, and circulating photographsthat areavailable to the many creative spirits who wish to narrate with images what happens from day to day on a young and vibrant continent. This impulse is maintained, in part, by the support that these artists find from their peers in the region, helping them move forward with projects, judged as collective efforts giving a sense of belonging to a common reality, full of minor differences.

*This text was written forthe catalogue that accompanies the window exhibition of contemporary photo books from Chile at the ICP Library, curated by Leandro Villaro.

Translated from the Spanish by Dale Shuger.

A window exhibition featuring a selection of contemporary photo books from Chile recently added to the ICP Library, curated by Leandro Villaro.

A book shelf of historic photo books from Chile from the library’s collection.Weinstein will discuss his own books [some will be available at ICP store for purchase] and the photo book scene in Chile.

Photographer Luis Weinstein was born in Santiago, Chile in 1957. He began freelancing in 1980 as an advertising and editorial photographer. Since then he has worked as a photojournalist, in television and as an editor, curator and producer of photography. He is a long time member of the AFI, Asociación de Fotógrafos Independientes, and was president in 1983, and member of the World Press Multimedia Contest Jury in 2014.Weinstein currently produces the International Festival of Photography at Valparaíso, and edits the South American photo magazine Sueño de la Razón. He is author of four photo books, and his own photographs have been exhibited internationally on numerous occasions.

[…] by Richard B. Woodward on why Vivian Maier’s own prints aren’t valuable, the other a post at the ICP blog by Chilean photographer Luis Weinstein on the historical and contemporary context for photography […]